Plant Breeders’ Rights

This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the Plant Breeders Rights Act in Australia.

Like most developed nations, Australia has a scheme for protecting the work of plant breeders via a scheme called Plant Breeder’s Rights or PBR.

PBR aims to provide an incentive for breeders to develop new cultivars (cultivated varieties) by granting an exclusive period to sell or licence that plant. PBR works much the same way as a patent; that is, that once a patent is registered, the inventor is granted the sole rights to sell or licence their invention until the patent expires. The income derived during this period provides a commercial return for the costs of developing the invention.

PBR has historically been contentious. Both home gardeners and commercial growers need to understand PBR laws in Australia and how they may affect their activities.

In light of the twentieth anniversary of the commencement of Plant Breeders Rights in Australia, I thought I’d look back at their history and introduction, as well as examining the implications for horticulturists, farmers and home gardeners.

History of PBR in Australia

Momentum for a PBR scheme in Australia started in the 1960’s following the meeting of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) 1961 and again in 1978. However, there were widespread concerns in Australia about the appropriateness of assigning rights over the use of plants, most particularly food crops. The predominant view was that food crops were a public resource and no-one should restrict their use. There was also a concern in Australia that the Commonwealth government didn’t have the constitutional right to enact a PBR and that the states would have to introduce their own schemes. Supporters of a scheme argued that a PBR scheme would provide an incentive for people to breed better plants that would lead to better food crops.

These matters were mostly resolved and by 1982, the Commonwealth introduced the Plant Variety Rights Bill 1982 into parliament. This contentious bill was referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Natural Resources which asked Prof. Alec Lazenby to investigate the needs of plant breeding in Australia. His report endorsed the introduction of such a scheme, but it was not until many years later that the Plant Variety Rights Act came into force.

Australia’s “Plant Variety Rights” scheme commenced on 1 May 1987. For the first time, plant breeders had a way to protect their financial investment in new cultivars. Customers at retail nurseries started noticing the new distinctive “PVR” logo appearing on plant labels warning them about the prohibitions on unlawful propagation or sale of the new varieties.

UPOV met again in 1991 and it was then decided that Australia’s PVR scheme would require significant revision. Following this, the Plant Breeder’s Rights Act 1994 was passed, supplanting the old PVR scheme with the new “Plant Breeder’s Rights” that commenced on 10 November 1994. This scheme is still in operation today.

According to IP Australia, the changes included:

- Tree and grapevine (Vitis vinifera) varieties receive PBR protection for 25 years from the date of granting, and in all other varieties, for 20 years from the date of granting.

- Sale in Australia, with the breeder’s consent, is permitted for up to one year prior to applying for PBR.

- Sale overseas, with the breeder’s consent, is permitted in tree and grapevine varieties for up to six years and in all other varieties for up to four years prior to applying for PBR in Australia.

- Farm-saved seed is allowed, unless the crop is declared by regulation to be one to which farm-saved seed does not apply.

- Intentional infringement of a plant breeder’s rights attracts a penalty of $85 000 for individuals and more for corporations.

- The concept of the essentially derived variety (EDV) was introduced. A breeder who believes such a situation has occurred is able to apply with us to have the second variety declared an essentially derived variety.

- Transgenic plants, algae and fungi could be protected.

- Plant variety rights granted under the old Plant Variety Rights Act 1987 are treated as if they had been granted under the PBR scheme.

What does PBR protect?

Plant Breeder’s Rights, if granted for a particular cultivar, prohibits the commercial propagation of that plant variety for the prescribed period unless the plant breeder has granted the grower a licence to do so. The breeder would also have exclusive rights to sell, import or export that cultivar. Other plant breeders can freely use parts of a registered PBR plant to experiment with, use non-commercially or develop a new variety for commercial use.

This means that home gardeners can propagate the plant for their own purposes, but cannot sell propagation material or whole plants. There are also provisions that allow farmers to collect and re-use seed in certain circumstances.

In order to qualify for PBR, a plant must be:

- Distinctive from other varieties of the same plant;

- Uniform and stable;

- Not have been exploited or sold outside certain time limits; and

- Have an identified breeder and an acceptable name.

Traditional varieties and naturally-occurring species, subspecies, varieties and forms are ineligible for registration. The plant must be protected by PBR in Australia in order for legal protection to apply. So, for instance, a plant that may be registered for PBR in the United States will not be legally protected in Australia unless that same cultivar is registered here.

In order to check, a database of PBR registrations is available from the Plant Breeders Rights Office at IP Australia. New PBR registrations are also published in the Plant Varieties Journal.

Labelling

One of the key requirements for protecting PBR is correct labelling. The Plant Breeders Rights Act 1994 requires that plants with PBR must be clearly marked as such. Under Section 57 of the Act, a court may refuse to award damages against a person in an action for infringement of PBR in a plant variety if the person was not aware of, and had no reasonable grounds for suspecting, the existence of that right.

The IP Australia website has instructions on how to label plants or seeds correctly. Only the approved text can be used:

Unauthorised commercial propagation or any sale, conditioning, export, import or stocking of propagating material of this variety is an infringement under the Plant Breeder’s Rights Act 1994.

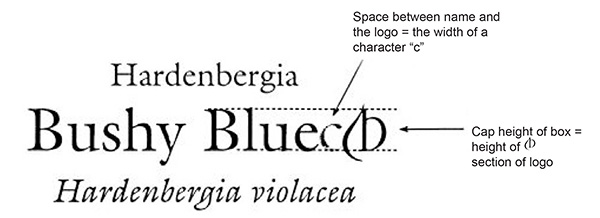

More importantly, the PBR logo must be displayed and spaced according to the requirements of IP Australia. (The instructions contradict themselves by using the wrong version of the PBR logo and ignore international nomenclatorial guidelines, but that’s a story for another day).

For horticultural websites owners, one of the easiest ways to mark PBR-protected plants online is with my Plant Breeder’s Webfont. The Plant Breeder’s Webfont is absolutely free and best of all, it will display the PBR logo inline as text – correctly spaced! (eg Acacia cognata ‘Mini Cog’ (PBR) ). Do have a look, but enough of the product placement – I digress.

The one important message to remember is that a plant without PBR protection isn’t necessarily unprotected. In Australia, plant varieties can also be protected by patents if their generation utilises a novel patentable process, but this is exceedingly rare. Usually, if a plant is not on the PBR list, it can be commercially propagated without concern. I have seen plants in retail nurseries with a warning appended to the label stating that “unauthorised propagation is prohibited” but without any PBR mark. As I understand it, such a warning is utterly meaningless and without legal standing in Australia unless protected by other forms of intellectual property.

One of the challenges of identifying PBR-protected plants in Australia is that a plant is permitted to have a cultivar name (its scientific identity) as well as a trade reference (which may or may not be a trademark) and a trademark. This can make a search of the PBR database difficult, so one needs to be vigilant when searching. A good illustrative example is the popular rose Flower Carpet® Scarlet, for which the scientific name is Rosa ‘NOA831OOB’ (PBR). This particular cultivar has a cultivar name (NOA831OOB), a trade reference (Flower Carpet Scarlet) and also features a registered Australian trademark (Flower Carpet®). All of these parameters should be searched in order to confirm that PBR does or does not apply to any particular plant, because the name that may be believed to be the cultivar name may not be at all.

For those eager to propagate ex-PBR protected cultivars, here’s an extra warning to heed (with an example). The PBR protection for the original Flower Carpet® Pink rose has expired. Whilst it is theoretically legal to commercially propagate this in Australia without a licence, one would only be able to sell it under its scientific name, that is, Rosa ‘Noatraum’. The breeder’s rights may have expired but the trademark certainly has not!

The moral of the story is that one needs to be careful when propagating plants. Nurserymen, horticulturists and home gardeners need to conduct thorough research before commercially exploiting novel plants.

Is PBR worth it?

This is an interesting question. One of the promises made when the original Plant Variety Rights scheme was introduced in 1987 (and repeated when it switched to PBR in 1994) was that protecting the intellectual property of plant breeders would provide an incentive for them to continue their work.

One phenomenon that I have noticed is the tendency for some large plant breeding firms to seek PBR protection in larger markets but ignore them in Australia. Two good examples are Osteospermum ecklonis ‘Zion Red’ (sold by one Australian grower as Flame) and Coreopsis verticillata ‘Route 66’ which are protected in the United States but do not appear on the Australian PBR register. This is clearly a commercial decision; the growers presumably decided that the cost of registering PBR in Australia would outweigh the financial return. Using these examples, one could argue that PBR in Australia is unnecessary as we receive some novel varieties from overseas regardless.

This is true, but our scheme is utilised by many more international companies that do seek PBR protection prior to selling in Australia. Without such a scheme in Australia, we’d miss out altogether. The PBR scheme also provides protection for our own domestic breeders so that they receive justified sales earnings to pay for their good work.

The Commonwealth Government undertook a review into the enforceability of PBR in Australia in 2010 and accepted a number of recommendations for change. Despite this, the government could see the value to industry and consumers of a PBR scheme in Australia. So whilst it may seem annoying and somewhat complicated, I believe that Australia’s Plant Breeders Rights scheme has its place.

As the scheme reaches its twentieth anniversary in its present form, we can look back and reflect on all the wonderful new plant varieties that Australia’s PBR scheme has enabled us to enjoy.

Disclaimer

Please refer to the Editorial Policy. The views expressed are my own and do not represent those of my employer. Anyone wishing to register a PBR should seek legal advice from a suitably qualified person or contact IP Australia.

References

Evans, P. & Haines, T. (2008) Plant Breeder’s Rights, Curtin University School of Law. (PDF)

Horticulture Australia Limited (2008) Plant Breeder’s Rights: A guide for horticulture industries. (PDF)

Sanderson, J. & Adams, K. (2008) Are Plant Breeder’s Rights outdated? A descriptive and empirical assessment of Plant Breeder’s Rights in Australia 1987-2007, Melbourne University Law Review, 32 (3): 980-1006 (PDF)

Stack, C. (2007) ‘Issues Paper: A review of enforcement of Plant Breeder’s Rights’, Advisory Council on Intellectual Property, Commonwealth Government of Australia. (Website)

Comments

One response to “Plant Breeders’ Rights”

Hi Adam,

very interesting article . Typically the nursery industry dont give a damn

The worldwide phenomenon that shits me is the very successfull genericism of trademarks

Eg Well after PBR has run out the trademark holder still monopolises the common name of the plant eg Flower Carpet Pink. ….so effectively PBR continues

Do you really think a nurseryman like myself would bother growing ‘Noatraum ‘ when no one including consumers and 95% of nurserypeople would recognise it

We have started a facebook site ”WHATS NOT ON THE LABEL”….Please join it

Cheers Jeff Koelewyn Hermitage Nursery 0437664432