Why Labor lost in Victoria

A considered review of the factors that lead to the Labor Party’s unexpected electoral loss in last weekend’s Victorian state election.

Year 2010 will be remembered as the year of inconclusiveness.

In March, a state election in Tasmania yielded a hung parliament. Later in August, a federal election delivered another hung parliament. In September, the Australian Football League’s Grand Final delivered a rare draw. So perhaps it should not have been too much of a surprise that Victoria’s state election last Saturday might have also delivered a similar result.

This time, however, the scales have tipped just that bit further and the Liberals have won, with a majority of 1 seat. John Brumby and his 11-year-old Labor government have been voted out of office.

From the beginning of the election campaign, John Brumby acknowledged that it would be a “tough contest” to win a record fourth term for Labor. To his credit, Brumby didn’t once refer to himself as an “underdog”, but I had the feeling that whilst he believed he’d lose a few seats, he didn’t think that the Liberals under Ted Ballieu could seriously threaten his government.

John Brumby probably reasoned that his was a good government: Crime was falling, the budget was in surplus and Victoria’s growth was steady. These may be correct, but his judgement certainly wasn’t.

Within an hour of tuning into ABC1’s election coverage, swings of between 6% and 9% were apparent in some seats. By 10PM, it appeared that Victoria would either have a hung parliament, or the first Liberal government since 1999.

On the night of the election, John Brumby told the Labor faithful “I know we have been sent a loud and clear message… To the people of this state who sent that message, we have heard that message, and I know we can do better in government”.

What that message was, we’ll never know because Mr. Brumby never got around to telling us. In any case, it was too late. The people of Victoria had made their decision.

Initially, Labor ministers dismissively stated that voters simply craved a change, as if there was nothing more to it than the proverbial “It’s Time factor” and nothing more. It almost suggested that the change was a whim. To me, this response is symptomatic of a government out-of-touch with its community.

For the most part, John Brumby’s (and before him, Steve Bracks’) administration were not that bad in themselves. The budget was kept in surplus, the state’s economy has continued to grow and service spending had continued to rise. But the government had managed to progressively irritate, almost offend, a large section of both rural and urban communities and seemed to show less and less willingness to admit to problems.

Brumby’s biggest problem was with his government’s water policies. Having left the water crisis to the proverbial last minute, there was almost a panic attack when Melbourne’s water supply reached 29% as a result of the drought. There was little concern when the water supply of the regions fell equally low, and the government seemed happy to place rural folk on Stage 4 restrictions. Melbourne, on the other hand, was treated to the dubious and less-onerous Stage 3A restrictions, which I have previously written about.

To ‘solve’ the water crisis, the government commissioned a massive desalination plant in Wonthaggi. Whilst the costs and secret contracts with the private operator became a political issue, Victorians seemed divided on the merits of the desalination plant itself.

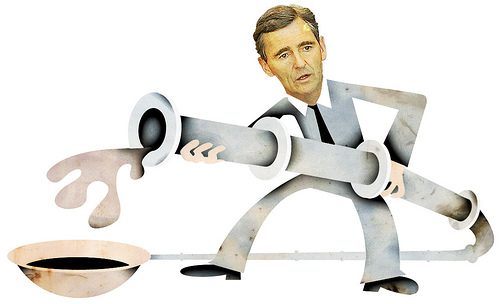

In contrast, the “North-South Pipeline” is arguably Victoria’s most detested infrastructure project ever.

The idea was that the open agricultural channels in the state’s north would be enclosed. A costly process, the state would pay for this and share the resulting water savings between the growers and Melbourne. To achieve this, a $700 million pipe was constructed to transport water from the Goulburn district to the city. Rural folk, whose very livelihoods depended on water for agricultural irrigation, were furious that their water was being piped to Melbourne to keep people’s gardens green. City folk were equally outraged that they were forced to take the ‘stolen’ water, and pay for it with massive increases in their water rates.

The authoritarian manner in which the government proceeded with the north-south pipeline project included sending in the police to arrest uncooperative landowners and a network of spies to monitor Plug The Pipe protesters. This didn’t go down well with the electorate and within months of the pipe’s completion, the drought ended and it is currently idle. I could make a witty ‘money down the drain’ pun at this point, but I shall resist.

If water raised emotions, transport wasn’t far behind.

Whilst in its first years in office Labor re-opened several regional rail lines that had been closed by Jeff Kennett’s government, they botched a fast rail project that was supposed to deliver a high-speed link between Melbourne and the regional cities of Ballarat, Bendigo, Geelong and Traralgon. Fast Rail was budgeted at $80 million (a ridiculous estimation) but ended-up costing $1 billion and the “fast” trains could only travel at 160km/h instead of the 300 km/h Japanese commuters are accustomed to. Worse still, sections of single-track were constructed where previously there had been two!

But the word that epitomises failure for John Brumby’s government is “Myki”.

The new ‘smart’ electronic ticketing system was supposed operate on trains, trams and buses, cost $494 million and commence operation in 2007. Instead, Myki was plagued with problems, cost $1.35 billion and only commenced on trains and trams several months ago. Many people questioned whether $1.35 billion could have been invested more wisely somewhere else.

Whilst water and transport policies were John Brumby’s biggest deficiencies, law-and-order isn’t ever far from any state election campaign.

Constant complaints about the lack of safety on the suburban rail system, as well as perceptions of inadequate policing started to resonate with many voters who felt unsafe when walking in the city at night or taking the trains after hours.

Perhaps as destructive for Labor as the policy failures were the numerous scandals, especially during the its last term.

The revelations that resulted from leaked memos describing how the Minister for Planning intended to hold sham public consultations as justification for rejecting a proposal to build a tower over the Windsor Hotel scandalised the state. Many Victorians were upset that the Windsor Hotel would be threatened, but were outraged at what appeared to be a deliberate attempt to sidestep normal processes. John Brumby’s refusal to establish an anti-corruption commission didn’t help to quell community suspicions that rot was starting to set-in.

Another scandal revolved around the proposed mandatory 2AM “lockout” from all pubs and clubs in Melbourne which attempted to see if something could be done about alcohol-fuelled violence.

With their income threatened, many pub and club owners took the government to VCAT and won, thus exempting themselves from the lockout. In the end, less than half of the licensed venues were involved and the project failed. Such an outcome could so easily have been avoided if the government had been strong and legislated away any right of appeal, but they didn’t, effectively sanctioning failure. Many people concluded that the government was more interested in alcohol taxes than tackling a serious social problem.

What finally damaged the government’s standing was the massive gas and electricity price rises (as much as 45%) that hit people where it hurt them the most. Combined with the horrendous stamp duty that home buyers pay on top of their over-inflated house prices and the massive rises in rents, the Victorian government failed to protect the people it was supposed to look-after.

Speaking to Jon Faine on ABC Radio 3LO this morning, former Labor Premier Steve Bracks said that the Victorian government had failed to respond to the issues of a growing population in Melbourne: “I think if there’s any lesson out of (the election result), it’s that we should have done better. We could have addressed the concerns of Victorians better. I think (voters) were saying, particularly down in the south-east corridor that … they wanted more back, they wanted less congestion (and) more opportunity to have a better lifestyle and I think that’s a fair judgement and we understand that.”

Bracks can see what it appears that Brumby can’t: That the quality of life of the average Victorian is being diminished, and the government was the main contributor. John Brumby became arrogant, believing that these concerns were no longer important. Now he’s paid the ultimate political price for taking the people for granted.

The new Premier, Ted Ballieu, has promised to do things differently. Having been sworn-in today by the Governor of Victoria, he will seek to recall the Parliament before Christmas in order to get some of his legislation passed. One item of business will be the formation of a Public Transport Authority to co-ordinate the state’s public transportation system.

Whether Ballieu succeeds or fails will depend on a range of factors. If he is wise, he’ll look at the lessons from Jeff Kennett in 1999 and John Brumby in 2010: That a Premier who becomes arrogant will lose touch, and a Premier who loses touch, loses office.

Comments

4 responses to “Why Labor lost in Victoria”

A good summary that would be quite publishable in a newspaper. I am pleased Bracks did not say the Brumby government, instead the Labor government, as most of the problems began on grew significantly under Bracks.

Re: Regional Fast Rail – it is not quite true to say they thought it would only cost $80m. They thought the *taxpayer* contribution would be $80m, and the rest would be raised via some kind of PPP.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regional_Fast_Rail_project#Costs

Daniel, you are correct. The $80 million was the taxpayer component of a proposed public-private partnership.

However, I still maintain that it was ridiculous to expect that the state’s contribution would be so small for (in commerical terms) an entirely unprofitable project. I also think it reflects very poorly on Labor that they were initially only prepared to spend a measly $80 million on a project of such economic importance to rural and regional Victoria.

I am sure we can agree that it was not a lack of available funds that was the cause of the miscalculation, but rather a miserly unwillingness to invest.

With all this rain Victoria gets just shows you how dumb State Governments are