Book review: Byzantium

Judith Herrin’s Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire takes the reader on an exciting journey through the eastern half of the Roman Empire.

For centuries, the Roman Empire controlled most of the ‘known world’ and shaped the continent that we now know as Europe. The common understanding of many Westerners is that the Roman Empire fell in 476 AD when it was sacked by ‘barbarians’. When, centuries later, Charlemagne established his Frankish kingdom in 800 AD, it came to be known as the Holy Roman Empire because it was supposed to have inherited the status of ’empire’ from ancient Rome. So powerful was the myth that Rome’s successor was the Holy Roman Empire that Westerners barely noticed that actual Rome hadn’t died.

The Roman Empire had been partitioned into ‘East’ and ‘West’ in the late fourth century and it was the western half that fell to the Vandals. The eastern half lived on and became known as Byzantium, although to its inhabitants it was still known as Rome and its citizens were emphatically Roman. Their capital had been established by Constantine (Rome’s first Christian emperor) before the fall of the west, and was named Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

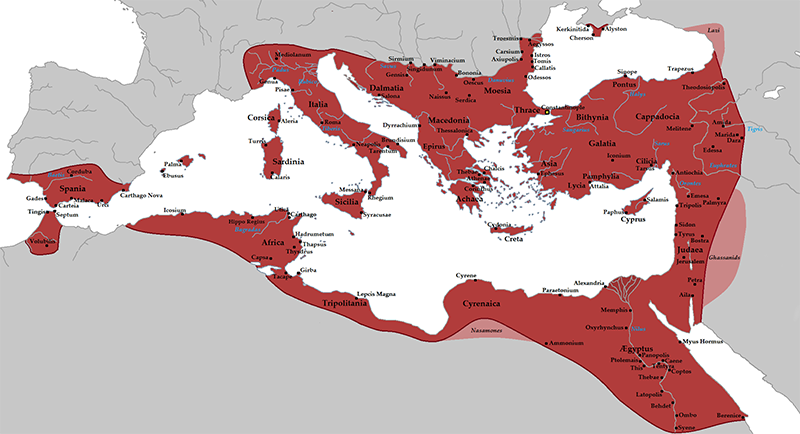

As the West plunged into darkness following Rome’s collapse, the East flourished as a centre for learning, a cultural hub, an economic powerhouse and the heart of the Christian faith. Byzantium’s lands were vast: at its greatest extent it covered areas contained in modern-day Spain, Italy, Hungary, Greece, Macedonia, Turkey, Iran, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt and Libya.

Judith Herrin’s book Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire documents the achievements of the Eastern Roman Empire as well as the many challenges that it faced.

Byzantium was almost always under threat. Constantine (and later emperors) ensured that the city was well fortified by a network of massive walls whilst the use of “Greek Fire” to incinerate opponents’ ships on the sea gave their navy a defensive advantage. Of course, Byzantium was more than a city and it was its vast regional territory that came under threat in the seventh century following the rise of Islam. The military success of the Arab Muslims took the Byzantine authorities by surprise and resulted in the loss of significant amounts of territory including Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine before the emperors took the threat seriously. Attempts were made to re-conquer lost cities (including Antioch and Jerusalem) without long-term success.

Byzantium had become the centre for Orthodox Christianity and often jostled with Rome for spiritual supremacy. When the Western Roman empire fell, some of the practices of Latin-speaking Christianity (what is now essentially Roman Catholicism) deviated from that of the Greek-speaking Byzantines. Certain cultural practices had changed over time (such as the use of unleavened bread for communion and the celibacy of all clergy in the West), but it was the filioque controversy that most strained relations.

Those of us in the West would be well familiar with this portion of the Nicene Creed which is stated during the Mass:

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

Nicene Creed (Modern English Translation)

who proceeds from the Father and the Son,

who with the Father and the Son is adored and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

Somehow, the Latin West added the phrase “and the Son” to the creed after the text was agreed by the universal church at an ecumenical council. The Orthodox church took considerable exception to this wording, because it challenged the stated understanding of the nature of Christ and the Trinity. The Patriarch of Constantinople and Byzantine emperor met with the Pope many times to try and reconcile this difference, without long-term success.

In the twenty-first century, it is difficult to understand how relatively minor differences in church practice and the wording of a single prayer could cause so much dispute, but Herrin does a good job of explaining the arguments and perspectives without losing the reader in deep theology. This episode is very important, because Orthodoxy was central to the very identity of the Byzantines, especially in the light of rivalry from the West and the threat of Islam from the east.

Whilst the filioque controversy was causing conflict with the West, an even deeper internal battle was to had within because it related to the Byzantines’ very sense of self: the use of icons (religious pictures). The practice of painting icons and using them in prayer was heavily ingrained in Orthodox prayer. But as Herrin tells us, the religious Byzantines started to question this central practice in the light of Islamic conquest of their lands. The citizens of Constantinople considered that their city was protected by the Virgin Mary and God’s grace, so the success of the Islamic “infidel” was a cause of great confusion. Why was God favouring the Infidel over good Christian people? The Byzantines concluded that they must have displeased God somehow. Quickly, attention turned to the Muslims’ prohibition on religious imagery and their military success which was contrasted with Christian practice. A decision was made that the use of icons had to cease in order to save the empire.

In the West, we’re well familiar with the destruction that occurred during the Protestant reformation, but a similar episode occurred much earlier in Byzantium. As Herrin tells us, people were outraged at the loss and destruction of their icons and alterations that were made to churches. The Pope was outraged, too. But the movement against icons, called Iconoclasm, was in full swing with imperial backing. Icons were destroyed in an attempt to save the city. In the end, Constantinople survived and the Orthodox church returned to using icons but this episode caused great trauma for three quarters of a century as both sides clashed.

Byzantium was always under threat, but it survived a long time because of its innovations and ingenuity. Herrin explains to the reader the importance of the Byzantine system of maintaining embassies with foreign powers and neighbours, be they friend or foe. This practice reduced the likelihood of war and fostered trade, which was central to the economy. For whilst many wanted to take Byzantium’s lands, they also valued its trading opportunities and its stable currency. Herrin passionately tells us about how Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city for centuries because of its trade links. Its education system, rooted in ancient Greek and Roman tradition, and the relatively high rates of literacy amongst its peoples put it at the forefront of Mediterranean societies. And despite its hostility with the Arabs to its east, it shared in their discoveries in mathematics and science to advance not only itself, but Europe too.

Herin makes the most compelling case that if it weren’t for Constantinople, Europe as we know it today could not exist. For Islam to be able to spread into Europe, it had to conquer Constantinople first. But the Queen City stood in the way; strong and defiant. For centuries the Arabs (and later the Seljuk Turks) tried to breach the city’s walls without success. Siege after siege failed. It was not until the fifteenth century that Constantinople eventually fell and Western Europe (and the Holy Roman Empire) had to seriously confront the threat of Islamic invasion.

So why, then, do we not hear more of Byzantium today?

Herrin makes the case that there are political reasons why the Byzantine empire has classically been regarded as a weak failure in the West. During the twelfth century, Byzantium joined the other European powers in the Crusades. These religious wars were aimed at taking back control of Jerusalem (and other cities) for Christianity and were composed of soldiers and peasants alike. It was during one of these crusades that the mobs called-in to Constantinople on the way south and control was lost for a variety of reasons. In considerable detail, Herrin describes the destruction as centuries’ worth of art, literature and architecture went up in flames as the mobs destroyed Constantinople. Worse still, the “Latins” took control of the city, imposing Latin Christianity over her people whilst exporting tonnes of their wealth back to Europe. Even if it survived another two centuries, Byzantium was never the same again and its people never forgot the pain of those events inflicted by the West.

How could the Christian West justify attacking their own brethren when the aim of their mission was to confront the Infidel?

Herrin posits that they couldn’t. So in order to explain this awful treachery, the authorities in the West made a case that the Byzantines deserved it. Their Orthodoxy was wrong. Their leaders were weak. Their embassies, rather than preserving peace, symbolised their collusion with the enemy. And so the case was made in the popular thinking that Byzantium was an undeserving, pitiful and worthless empire.

Herrin provides a thoroughly readable account of Byzantine history, which starts and ends with a tale about how a couple of construction workers at her university had found themselves in conversation with her about Byzantium after seeing the nameplate on her office door. In writing Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire, she never loses sight of the original purpose of the book which is to make the story of Byzantium accessible and engaging to a lay audience. This, she achieves with great success.

Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire is a leisurely read through late antique and medieval history. Her writing style is personal, even passionate at times yet shows great depth. Herrin’s greatest strength lies in her ability to explain complex theological concepts to a lay readership.

For all the engrossing stories of achievement, failure and intrigue that defined the story of Constantinople, her emperors and her people, Herrin saves her most impassioned plea to the end:

So if we need a word to describe the mendacity of our present political leaders, the bizarre incompetence of our own bureaucracies, the cunning selfishness and illegal mechanisms of our great corporations, or the intricate glamour of our global corridors of fame, then we should find the appropriate, modern adjective – and it is not ‘Byzantine’. The empire was not without its corruption, cruelty and barbarities, far from it, but by projecting onto it the notions which are still insinuated by the term ‘Byzantine’, we suggest that these failings belong to some remote and doomed society, foreign to our character and quite unconnected with our own traditions.

Herrin is correct. Ignorance of the Eastern Roman Empire is widespread in the West and ‘Byzantine’ has become a pejorative term. Hopefully Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire can change this negative perception for the better.

Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire (ISBN 9780 141 031026) is published by Penguin.

Comments

No comments have yet been submitted. Be the first!